States build support for newspapers; how to tell your story

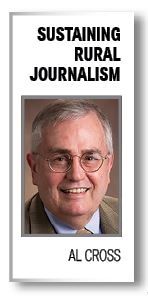

Al Cross

May 1, 2023

Newspapers and other local media seeking help through changes in government policies have turned their attention to state governments, after coming close last year in a Congress that is now less likely to help them. But how will they make their case to 50 state legislatures?

There was encouraging news in April as the Washington State Legislature eliminated its 0.35% gross-receipts tax on newspapers and certain digital publishers for 10 years. But one legislature does not a trend make, and many lobbying interests are always seeking tax breaks.

Newspapers’ financial challenges are widely known, but only in a general sense. When local newspapers write about their problems, it might seem self-serving. But what if legislators in a state could read a comprehensive report about the newspapers in that state, including information about papers with which they are familiar?

The Commonwealth of Virginia got such a report last month from The Rappahannock News, a small weekly newspaper in a northern Virginia county of 7,500 people, and the Foothills Forum, a local foundation led by journalism retirees that finances specialized reporting in the Rapp News, often from experienced journalists with experience in nearby Washington, D.C.

Few newspapers will be able to replicate the favorable situation of the Rapp News, but the report by Christopher Connell, former assistant chief of the Washington bureau of The Associated Press, provides a template that larger news organizations, state press associations, academic institutions and other nonprofits could use to tell the story of newspapers, their needs and why they’re needed.

The report is at https://tinyurl.com/3n7e4nfx. Under the headline, “As some newspapers struggle, local news is harder to find in Virginia,” Connell reports that about 42 Virginia newspapers closed or were merged into other papers since 2004, “and that total doesn’t include several other weeklies that closed or merged this year.” The figure comes from the State of Local News Initiative, started by Penny Abernathy at the University of North Carolina, now at Northwestern University.

“Those still standing have suffered deep staff cuts,” Connell reports. “Many of the bigger papers have retreated from parts of the state they used to cover from satellite bureaus. Now they only pay attention outside their market when something big happens, like a natural disaster or juicy scandal.”

But do the people of Virginia realize what's going on?

Clark Hoyt, retired vice president of the Knight-Ridder chain that sold to The McClatchy Co. in 2006, told Connell, “People aren’t really aware of the extent to which traditional journalism, with a set of values and proper procedures, has wilted away. You don’t have people covering school boards, city and county commissions, courthouses and police departments on a regular basis.”

Connell’s main story includes several examples of what happens when a local newspaper closes. Sidebars look at leaders in Virginia local news, and the package includes an editorial, “Let's work together to save Virginia local news” and a column by Publisher Dennis Brack about the Rapp News: “Thanks to you, your local news institution is strong.”

One of the leaders profiled (at https://tinyurl.com/n69a9dc6) is Publisher Anne Adams of The Recorder in the mountain town of Monterey, long a great example of good journalism being done under challenging circumstances. That has been especially true in the last five years.

“The newspaper’s precarious finances pre-dated COVID,” Connell reports. “In 2017, it raised its newsstand price from $2 to $5 and more than doubled the yearly subscription rate by mail to $99. It was a bold move, but “We just came to the conclusion that if advertisers are not going to support us, readers are going to need to,” Adams said, and they did. “We had very few complaints because we completely overhauled the newspaper, added more color and did other things to make it worth their while.”

Then came COVID, and “Things came screeching to a halt,” Adams recalled. “This is a heavy tourism-related area. Restaurants shut down, bed and breakfasts shut down, the Homestead resort shut down, and Bath was the county with the highest unemployment rate in Virginia. It was a mess.”

Again, readers rescued the paper. Adams told Connell:

“I wrote an editorial, told them what was going on and said, ‘All I can do is ask your support.’ And we gave them some options like, ‘Hey, why don't you consider buying a subscription for somebody who’s unemployed ... or buy an ad for a business that's suffering? Or just donate.’ My readers came through in droves. It was remarkable. We had a 99-year-old woman who sent $25 and wrote, ‘Take $5, go get yourself a cup of coffee and put the rest to the paper.’”

The donations and federal pandemic relief funds enabled Adams to keep her staff together.

The Rapp News package advanced the April 20-21 Virginia Local News Summit, called by Foothills Forum, Virginia Humanities and the University of Virginia’s Karsh Institute of Democracy to discuss “what to do about the crisis in local news coverage,” Connell writes.

Larry “Bud” Meyer, a former Knight Foundation official who co-founded Foothills Forum and chaired the summit’s advisory committee, wrote in the package’s editorial that the erosion of local news “loosens the guardrails of our democracy and diminishes our ability to appreciate the history, cultures and traditions of Virginians.” That’s the sort of state-based appeal that can build support for newspapers.

Who will tell the story of newspapers in your state?

Al Cross edited and managed rural newspapers before covering politics for the Louisville Courier Journal and serving as president of the Society of Professional Journalists. He directs the University of Kentucky’s Institute for Rural Journalism. It publishes The Rural Blog, from which this was adapted. For more information, write al.cross@uky.edu.