National Summit on Journalism in Rural America explores local news crisis in smaller markets

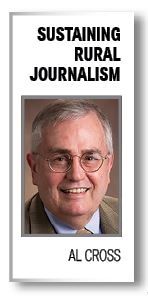

Al Cross

Aug 1, 2023

The “local news crisis” is real, but it might be mis-described.

The standard metric for the crisis is the decreasing number of newspapers, but more than 90% of U.S. counties still have at least one paper. The forces that are causing closures or mergers are having a greater effect on quality than quantity, creating “ghost newspapers” that often lack a physical presence and fail to serve its interests with news coverage needed to support local democracy, civics and business.

The more serious quantity problem is on the demand side, not the supply side. Fewer citizens are interested enough in local news to buy or subscribe to a newspaper; they think they can get the “news” they need from free sources, without regard to those sources’ reliability.

But many, if not most, communities still have enough citizens who understand what quality news is, and there are startup and legacy news outlets who know how to serve them. We heard evidence of that, and urgings for change, at the National Summit on Journalism in Rural America, held June 7 in Lexington, Kentucky, and online.

Digital and print startups are finding success where ghost newspapers are failing their communities. One of the nation’s newest and largest newspaper chains consists mainly of former Gannett Co. newspapers, many of them ghosts that are being revived. Smart, independent owners are finding new ways to generate revenue and are testing the nonprofit world. More newspapers are going nonprofit to survive.

One of the best testimonies of the demand for local news was a session with four women who are finding startup success in markets no longer well-served by chain-owned dailies. Two have for-profit papers: Lynne Campbell of The Community News in Macomb, Illinois, and Debra Tobin of the Logan-Hocking Times in Logan, Ohio. Two have non-profit, digital-only news outlets: Jennifer P. Brown of the Hoptown Chronicle in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, and Nicole DeCriscio Bowe of The Owen News in Spencer, Indiana, which is just getting started but has support from the local community foundation and Chamber of Commerce.

Brown was editor of the Kentucky New Era, which she quit before it was sold to Paxton Media, which closed the New Era’s office. But Hopkinsville has two radio stations that do news, and “I've learned that it really doesn't work for me to try to compete against the other local media. It's a lot of wasted energy,” she said. “What I really wanted to do was give people stories where I could sort of flex my institutional knowledge of the community and provide context and background that maybe they felt like they weren't getting in other places.”

Tobin, a longtime editor-manager for Adams Publishing Group in southeast Ohio, started the Logan-Hocking Times in a county of 46,000 as a digital outlet, selling subscriptions for $7.99 a month. Now she has more than 1,000 subscribers and has started a free-circulation weekly print edition because many people in the county don’t have computers or broadband.

Campbell owns the Community News in Macomb, Illinois, which has the legal advertising in McDonald County, population 27,000, because Gannett’s McDonald County Voice is down to a few hundred subscribers, she said. Once a free-circulation, pickup product, her paper now has about 1,000 subscribers but publishes a free midweek edition in addition to its Tuesday and Friday editions. A former regional publisher for GateHouse Media, which bought Gannett, Campbell said that when she quit that company, “I made it my mission in life to save community newspapers.” (More on the session is at https://tinyurl.com/cvbafckv.)

Jeremy Gulban is trying to revive former Gannett ghosts. His CherryRoad Media has 77 papers, more than 50 bought from Gannett, which ran many of them into the ground. He said he has restored local editorial control and eliminated most non-local content, “invested more in editorial positions” and "tried to make sure we have a local ad rep in every market," he said. "We've had a hard time getting people. . . . Our biggest source of talent, believe it or not, is just people who used to work at the paper, and see that it's improved and want to come back."

Local has its limits. Local ad and page designers are "a luxury that we can't afford," and some papers still have no local office, he said. In Stephenville, Texas, "We're trying to pioneer like a shared office, you know, with a Chamber of Commerce, maybe even a local restaurant, you know, we're open for lunch three days a week.” Community engagement is important, because "The success or failure of these rural newspapers is on the local people," he said. More on his presentation is at https://tinyurl.com/5bhx5xnf.

Engagement is easier for local owners like David Woronoff of The Pilot in Southern Pines, N.C., which may have the most diverse revenue base of any U.S. weekly; 56% of its revenue comes from magazines, mostly non-local, and it also has a daily email newsletter, a digital consultancy and a bookstore.

"If the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. If the only tool you have is a newspaper, then the solution to all of your community's information and marketing needs is going to be – surprise, surprise – more newspaper,” Woronoff said. “We're in the community-building business, and news just happens to be the service we render. ... In a relatively rural community, we have an 11-person newsroom. ... We're able to produce that sort of journalistic heft because we have expanded beyond just being a newspaper."

On the same panel with Woronoff was Jack Rooney, managing editor for audience development of The Keene Sentinel in New Hampshire. The locally owned daily started a Health Reporting Lab, which "operates as a nonprofit, essentially," as "a testing ground to develop new ideas and find ways to reach new audiences and grow revenue," Rooney said. It’s donor-financed, through grants than range from “high dollar” to “constant crowdfunding," he said. More on the session is at https://tinyurl.com/2s47ea5b.

Ross McDuffie is the chief portfolio officer for the National Trust for Local News, which made news and enlarged its portfolio in June by buying most of Maine’s newspapers and is working toward similar purchases in other states. He said a nonprofit umbrella organization "creates the scale without trivializing the localness that makes these organizations special and essential to the communities that they serve. . . . You unlock efficiencies of scale while keeping quality local news as its North Star,” not “profit or shareholder value.”

McDuffie’s remarks (details at https://tinyurl.com/3prdb48n) came with his report on a survey of 39 rural newspaper publishers that found 10 of them did not expect to be in operation five years from now, while only one expressed concern that their newspaper would close in the next 12 months. The survey was conducted online June 6-23. McDuffie acknowledged respondents "are likely going to be more optimistic, and wanting to share that."

The survey found that 15% of the publishers' newspapers had no digital presence at all, and "over half had fewer than 500 digital paying subscribers," McDuffie said. "These results point to a lot of work that's needed, but I'm an optimistic guy, and I see a lot of room for optimism here. . . . There's lots of room for growth in revenue diversification."

But too many rural publishers show "a pronounced lack of urgency as they await a clear, proven path to follow," University of Missouri journalism professor Nick Mathews said. His research with other academics in the Great Plains “reveals a profound grip of fear in rural weekly newsrooms, leaving leaders in a paralyzing state of inaction and risk aversion.”

With the help of grants, Mathews and his colleagues got Joey Young of Kansas Publishing Ventures, which owns three weeklies in south-central Kansas, to experiment with alternative revenue sources. Young reported that they are seeing growth in circulation primarily through email newsletters that require a subscription to the newspaper.

Faced with the need for more revenue, Young and his wife Lindsey published a story with graphics called "The cost to print," explaining why they needed to raise their annual subscription price above $50 and the single-copy price above $1.50: "Our costs have gone up largely somewhere between 38 and 42% in the last two years."

That cleared the way for a big increase, to $144 a year, and the start of an online paper as an alternative. "Almost all of our readers who contacted me said, 'We want the print product. Just charge us more'," Young said. "We did our first round of renewals this past month, and . . . we have the exact number of renewals that we normally would. It's a small sample size, but so far everything's been fine." More on the Young-Mathews session is at https://tinyurl.com/2f2enhe6.

Mathews, noting that he had been regional editor of three daily papers and three weeklies, concluded, "I'm gonna leave you with one last plea. I beg of you. Newsroom leaders must recognize that remaining stagnant, idle and believing, even if not saying that nothing is wrong, is wrong. The choice of inaction is not a viable choice."

Al Cross edited and managed rural newspapers before covering politics for the Louisville Courier Journal and serving as president of the Society of Professional Journalists. He directs the University of Kentucky’s Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues. He’s at al.cross@uky.edu.